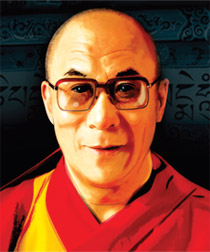

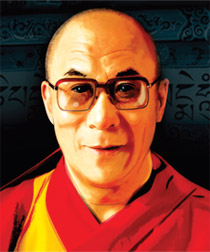

Nothing had prepared me for the total worship of a living human being that I witnessed the first time I saw the Dalai Lama surrounded by a crowd of Tibetans. He had invited me to film his visit to Bodh Gayā, the place of Buddha’s enlightenment and Buddhism’s most holy site, in the northeast Indian state of Bihar. As this beaming, saffron-robed monk shuffled quietly along the road toward the tree under which Buddha Sakyamuni is said to have achieved enlightenment, tens of thousands of people lined the road in various states of devotional delirium. Some had endured arctic temperatures and Chinese snipers to traverse the Himalayas from Tibet. Others had ventured out of rural Himalayan villages in northern India for the first time. Many had saved for years for the two-day train journey from their homes in the south. Old men, wrapped in skins, who had spent their lives herding yaks on the Tibetan plateau cried uncontrollably, overwhelmed at the first sight of a man who to them is a direct reincarnation of God. The crowd, straining every muscle to get a brief touch of his robe and increase their chances of a better rebirth, was violently thrown back by Indian police as the Dalai Lama passed.

It was unlike anything I had experienced before or have since: such extreme fervor of religious devotion for a single man. How, I wondered, could this gentle, mild-mannered monk support such a high level of expectation? “I’ve never seen anything like this in my life. How do you deal with it?” I ask. He thinks for a few moments, apparently oblivious to the small riot developing from this brief delay (and much to the aggravation of the Indian police and a wandering cow). “I’m carrying Buddha’s message,” he finally replies. “People have affinity for Buddha, and therefore they have affinity for me.”

The humility was characteristically disarming, a conscientious wearing of the crown combined with heartfelt embracing of what it stands for. But was this level of expectation not onerous to him and surely oppressive at times? Several months earlier, on a sunny afternoon outside his residence in Dharamsala, where the Indian government granted him refuge in 1959, he is giving his usual audience to a stream of Tibetans in an atmosphere that seems to combine tea at Buckingham Palace with a visit to Santa’s grotto. Two young parents carry a three-year-old girl, offering her up for the Dalai Lama’s blessing. Her arm is broken, and her face is twisted by fear and pain. “Only you can save her, Holiness,” they intone, the color bled from usually rosy, windswept faces. A rare frown descends over the Dalai Lama’s face. I’m sure I see impatience and annoyance, combined with the headmasterly authority that characterizes his bearing on these occasions. “Take her to the hospital immediately,” he instructs an attendant monk, who spirits them away, their anguished figures replaced immediately by the beaming toothless smile of the next septuagenarian devotee.

The surrealism of the episode sits uncomfortably with the reality that such extreme acts of devotion are underpinned by a widespread belief among Tibetans that the man possesses superhuman powers. He is expected to provide spiritual sustenance to a nation of exiles and lead them back to their homeland, which is currently in the grip of one of the mightiest and most authoritarian regimes on the planet. Without him, the Tibetan cause would be weakened beyond recognition, leaving Tibetans everywhere distraught and despondent about the future. When he says to me that thousands of Chinese and Tibetans will commit suicide when he dies, I ask him how that makes him feel, pushing to breach the stoic façade of this generous, gentle man. Another pause, a mischievous twinkle, the hint of a laugh: “It makes me determined to live.”

The good humor, I’m certain, is sweetening the pill—he is a master of the witty but heartfelt riposte. For he knows the enormity of who he is and the difficulty of his position, the seemingly unattainable nature of the hopes he must shoulder. “People have unrealistic expectations of me,” he concedes to me rather unnecessarily after the broken arm episode. I catch myself speculating about why he is so quick to embrace the interminable conveyor belt of Westerners who visit him and for whom he crosses the world addressing legislative assemblies, Buddhist conventions, interdisciplinary science platforms, and interfaith synods. Perhaps the relative normality with which he is treated in the West provides relief from the intensity of devotion showered on him by Tibetans, who regard him as totally superior to themselves, otherworldly, an object of sanctity rather than a peer or friend.

He has certainly embraced me. After the early challenges of getting clearance for the film—this is the only documentary for which he has granted truly unencumbered access—he is an extraordinarily generous contributor. Though he asks me to stop filming for rare moments—usually during discussions with Chinese envoys—he generally ignores the camera, apparently oblivious to when we are filming, and allows me to accompany him everywhere. To my great surprise and even greater satisfaction, he seems to warm to my companionship and that of the crew, at times expertly confounding my identity with that of the camera through a plethora of good-humored witty asides, keeping us abreast of what is happening and almost always taking time for my questions.