I remember this one Sunday afternoon in 1988 with the sharp vividness that memory usually reserves for truly significant or disastrous events. But this was such a small thing. I was in the bathtub reading the New York Times when I came across an announcement stating that the weekly “Hers” column, which was the only place in the whole newspaper that specifically reflected women’s thinking, would no longer appear every week because, in the name of equity, it would alternate with a new “About Men” column. To my own surprise, I burst into tears, sobbing almost uncontrollably. My partner came running, wondering what calamity could possibly have befallen me in the bathtub. He laughed when I told him what my trouble was. “But don’t you get it?” I cried. “The entire New York Times is about men!”

I don’t know why I had such a strong reaction to this—maybe because it was a definitive sign that the fresh inrush of women’s concerns that had flooded into the mainstream since the sixties was slowing to a trickle, mixing with everything else, losing its bracing quality. I’m sure my response was unusual, but it touches on an experience shared by so many women: the strange, sometimes enraging sense of living in a culture that rarely reflects one’s priorities, concerns, and deeper desires. Despite the progress made in these last four decades, Western culture still suffers from male bias—from Our Father in Heaven and the occupants of the Oval Office to the ravaging of Mother Nature and the ever-intensifying sexual objectification of women (and girls). The recipe for cultural change has been pretty much “add women and stir”—as if reaching some balance in the numbers of men and women in public life, which has not even happened, would transform the basic ethos of our culture and shift the course of history.

Over the last twenty years, however, something deeper has started stirring in women, a motivation to change culture at its roots. The goal is to create a new spiritual and ethical context that would balance and heal our hypermasculine world through honoring the feminine as sacred. This means a variety of things, and different women (or groups of women) have identified the feminine in different ways. There are some who see the Divine Feminine in the unique life-sustaining roles that have emerged from our biological role as mothers. Others speak of a feminine principle that is a force in the human psyche and a fundamental aspect of the manifest world. And still others are engaged in reclaiming or re-creating rituals to celebrate ancient goddesses, to make this feminine divinity more visible and conscious. Common to all (or most) is the sense that the sacred is not to be found in a transcendent realm out there somewhere but that the sacred is immanent to life. Thus these forms of spirituality celebrate the very human endeavor of trying to realize unity with nature and with one another—often celebrating the body, sexuality, and relationship.

All told, it’s an unprecedented phenomenon. Never before in Western history have women actively insisted that the sacred dimension of life reflect their (our) gender. And from what I can tell, the same generation of women who advocated for social change in the last century—my boomer sisters—are the vast majority of those engaged in this experiment in cultural and consciousness change.

In response to a recent issue of this magazine, Woman: A Cultural, Philosophical, and Spiritual Exploration, quite a few women (and men) wrote us to point out that the next step for women, and our culture, is a reclamation of the feminine. There is no doubt that, at this point, many of the ills of our world come from an emphasis on the more negative aspects of masculinity that have come forth in modernity—rationality divorced from human connection, competition, hierarchies of power over others, and separation on multiple dimensions. But what does it mean to say that the feminine is the answer? This too easily sets up a polarizing dichotomy of its own—equating the masculine with what is bad and the feminine with good. And while the “masculine” and “feminine” are not synonymous with “man” and “woman,” we know that they are very much related. We can’t forget that women and men created history together—including the structures of patriarchy that we now see as so destructive. Given how strongly some of our readers felt about the need to bring forward the feminine, however, I began to wonder if I actually understood what they meant or if I had overlooked something. Or perhaps it is just semantics, and we are speaking about the same thing but using different terminology. We all share a desire to move beyond patriarchy and see that as critical to our individual and collective evolution (or even survival). The question that I want to address is: How do we create a postpatriarchal culture? And how does that relate to the Divine Feminine or feminine principle?

The Feminine Principle

From what I gather, most of these new woman-created spiritual paths implicitly or explicitly rely on the groundbreaking theoretical work of psychiatrist Carl Jung (1875–1961). Jung, who pioneered the theory that all of humanity shares a deep psychic realm that he called the collective unconscious, assumed that the feminine and masculine are ontological principles so profound to life that one could easily see them as inherently sacred. They describe two fundamental ways of being, two types of psychic energy, often represented by female and male images called archetypes. The masculine doesn’t necessarily mean men, nor the feminine women, but they are closely related, because at the physical level, the female body is an expression of the feminine principle and the male body is the expression of the masculine principle. Jung saw archetypes as “images of the instincts” and therefore as universal, operating in the psyches of every human being. According to Jungian analysis, archetypal images appear in dream and myth. They are rooted in our unique individual histories as well as in the collective unconscious, the shared reservoir of humanity’s journey. That is why images of the mother are so prevalent in our dreams and symbols—each of us has a mother, and every generation of humans has been mothered. More importantly, perhaps, Jung believed that the archetypes come from a more essential realm of existence, and through their interactions with us in dreams and symbols, they can guide us.

While the difference between the masculine and feminine may seem self-evident, I haven’t found it to be all that clear. Some, like Ken Wilber, note that men are more naturally aligned with Eros, which he considers to be the creative instinct, and that women are more aligned with Agape, compassion. Others divide Being and Doing into feminine and masculine, respectively. Jung apparently believed that the feminine was Eros and the masculine Logos, which crudely corresponds with emotions and intellect. Jung’s preeminent student, Erich Neumann, argued that the masculine is focused consciousness and the feminine is diffuse awareness. Generally, it seems, the masculine is related to agency, assertion, and intense directed focus, and the feminine is related to receptivity, containment, and an encompassing depth of being, both of which are related to the reproductive roles men and women have played since time immemorial. They are psychological expressions of our bodies—men up and out, women down and in.

That our bodies are the fundamental substrate through which we create our sense of self is no surprise. The pioneering developmental psychologist Jean Piaget and his wife, Valentine Châtenay, carefully documented how the capacity for abstraction, including speech, is built on infants’ bodily engagement with objects and people. Erik Erikson, a protégéeric of Anna Freud, noted decades ago that when boys and girls play with blocks, boys tend to build towers and girls create enclosures. One’s bodily experience in infancy, mediated by culture, forms the deepest layer of self, which is why so many brilliant psychological explorers—such as Piaget and Erikson, as well as Freud, Margaret Mahler, Daniel Stern, Jacques Lacan, and many more—have tried so hard to understand how this happens. Even before research showed how male and female brains were wired differently, the fact that certain personality qualities or characteristics would be consistently found in women or men made sense because of our different bodily experience. This is expressed in culture in myriad ways—from the desire expressed by so many men throughout history to penetrate into new territory or the desire in women to create and decorate homes. Our experience of being differently embodied has shaped our psyches and our culture.

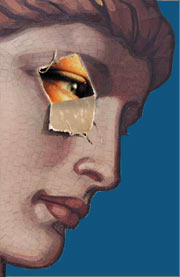

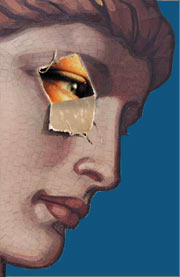

The issue of embodiment, and how it determines who we are as women and men, has been a long-time interest of mine. My academic work, as part of Carol Gilligan’s research collaborative on women’s and girls’ development, was about embodiment and the different way of knowing that girls and women have, compared with the norms of male culture. I saw how as girls’ bodies mature and their minds develop the capacity to holistically grasp cultural ideals and expectations for women, they “hit the wall of patriarchal culture,” as we called it, and cut off from themselves in order to pass through its narrow door. Most of us have learned that if we want to have success, be attractive, and feel secure, we have to dissociate from certain feelings (such as anger or vulnerability), from a real connection to sexuality, and from our own perspective on reality. We have learned how to create ourselves as objects in male culture. Paradoxically, the focus of our subjectivity has been a self-objectification, constantly reflecting the image (or images) that will get us what we want. For girls not to have to go through this dark passage to become women in patriarchy, we women would have to undo these dissociations to find a new, whole sense of ourselves.

That’s why I’m puzzled when I hear that the feminine principle is rooted in the experience of embodiment—or is embodiment itself. From a certain point of view, my value as a woman in patriarchy has only ever been about my body or my capacity to have sex and to bear and nurture children. Women’s souls and spirits are shaped to be nurturing vessels and to exist in relationship—which makes this our deepest level of conditioning, one that is almost completely unconscious. Resorting to traits that have developed in women, by virtue of our capacity to give birth and nurture life, over the thousands of years in which our primary value has been to reproduce doesn’t seem to get us beyond patriarchy. How, then, would bringing forth the feminine principle—if it is rooted in this most conditioned aspect of self—take us to a new culture?