Feminism is the radical idea that women are human beings. Years ago, I bought a button with this slogan on it at a conference because I found the saying both poignant and outrageous—funny, sad and maddening. On the face of it, it seemed nonsensical. Of course women are human beings. Did it need to be said? Yet, there was the rub. Somehow it did. I didn't take this to mean that men held the secret of "human being," but there certainly was some very real way that, in the world in which we all lived, who men were and what they did mattered in a way that wasn't available to women.

And I stood at ground zero, the center of a seismic movement, a wave of righteous rage and blazing passion that was going to tear up the very ground where we all stood, rip the moldy fabric of society and forge new bonds between women and between women and men to create an entirely new, unknown possibility for both women and men to matter. Nothing else on the planet was important but this. This was the movement for women's liberation in the late seventies and early eighties. I was part of it; I was a feminist. This was utter, complete

revolution.

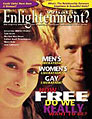

Or so I thought. Something happened on the way to the revolution. It didn't happen. Not that the social world hasn't changed somewhat, but the radical promise of women's liberation for all humanity has been swallowed up by the status quo without much more than a bit of indigestion now and again. In my naïveté and fervor, I would never have predicted that. Nor would I have predicted that I would be thrilled to interview a

man about true human liberation beyond gender. Twenty years ago, had someone made that prediction, I would have laughed—

oh, yeah, right! Amazingly, much to my surprise and joy, Andrew Cohen's call for the total, absolute liberation of women and men holds the true promise of revolution that the women's movement only hinted at.

Feminism is the radical idea that women are human beings. I don't know when the term "feminism" was first used, but in the popular press, and in my high school, the movement or ideology or hope for women's freedom was known as "women's lib" (or, too often, "women's lip"). "Feminism" seemed to take the word "feminine" and give it a kick. But a difference has evolved between women's liberation and feminism. In the past twenty years, women's liberation, a movement for social change, became feminism, an ideology. In that transition, it moved (as I did, too) from the streets into the academy, from whispers in the women's room to endless discourse in gender studies, from a nuanced realization of shared experience to an aggressive individualism further fragmented by identity politics. I began to fear that feminism was rapidly becoming a confusing set of ideas that divided us as human beings. Somehow, the passion had gone out of the revolution.

For me, the movement had always been about passion. It seemed perfectly obvious to me, from a very early age, that something was very wrong between men and women. My mother, smart and strong as

she was, was a victim and my father, as sweet and funny as he could be,

really wanted it that way—even to the point of getting pleasure out of his dominance. Even as I sided with my mother, I never lost touch with the pain evident in my father's stance of domination. Women's liberation obviously had to be a movement to liberate women

and men from the distortions and limitations that turned us into dangerous strangers, the Other to each other. From where I stood, it never was a competition between women and men. It wasn't a zero-sum game: If women win freedom, men then lose. Yes, we were often angry (and some of us, unfortunately, still are) as we came to see just how deep and how oppressive is this system accurately called "patriarchy." And that anger was often directed at men. But feminism's radical idea didn't mean that men were either the enemy or the standard for human being. To me, it meant that I

knew in the deepest part of myself that what was happening between men and women, who men are and who women are, had to change and

could change. And that it would transform life as we know it.

But what was that change? Did it mean that men and women were simply human beings and there would no longer be a sense of men as a group or women as a group? Then the differences

among men and women would be as pronounced as those

between men and women. Or did men and women being human beings mean that women then could have access to all of what men had (which would make what men were doing now the standard for human being)? Did it mean that women's roles should be valued as basic cultural values, not just relegated to the ghetto of women's work? If so, an unimaginable shift would have to occur at every level of society.

It

was beyond the imagination. We were trying to dig into something that was so core in all of us that we had no perspective. How could we tell what was real, true, authentic from what we had learned? The contradictions began to pile up. I remember a colleague working on a landmark case about domestic violence who told me of another woman lawyer on the case breaking down at one point because nearly every night when she went home, she was harassed and beaten by her husband. Or our constant struggle to keep women a priority while in a relationship with a man. Or the endless, often unvoiced conflict and falsehood among ourselves as "sisters"—and the rifts between us based on differences in race, ethnicity and class. The deeper we went, the more resistance there was—and often that resistance was in ourselves. Feminism's idea lost its radical edge and revolutionary passion as we all found out that change was hard. We wanted what was familiar: We felt secure in playing sexual games, depending on men, having power as mothers.

Feminism has no answer to the question: What self is it that's liberated? Our imaginations couldn't go beyond what we knew—male roles or female roles, traditional masculinity or femininity, or some form of androgyny that is both together. Yes, feminism may be the radical idea that women are human beings, but the sixty-four-thousand-dollar question is: What does it mean to be a human being? Over the last twenty years, feminists have come to different conclusions about what this means. Some are just beginning to say aloud what they whispered in private: My god, do you think it's all

biology? In this, we are simply intelligent animals who, with our enormous brains, have the possibility to transcend our lower nature, but it's useless to fight those biological drives that set men and women apart. And others have held on to the view that who we are is all a social construction, that everything that we are—from what we think to how we walk to what we value to how we experience ourselves in our bodies—has been learned from culture. There is nothing that is

truly masculine or feminine. In fact, there is nothing real, true or authentic about us at all because we've been socially constructed. In this view, liberation comes from creating ourselves anew—getting our own construction permit, deconstructing the old self and making ourselves into whoever or whatever we want to be. One construction is as good

as another because nothing in our experience has any inherent truth or reality to it. Our only guide to self-invention, according to postmodern gender theory, is pleasure—whatever feels good, exciting, forbidden. We are free to play or perform genders, to do whatever we want without shame just because it's a thrill. Neither of these views, to me, held forth the promise of human being that I had experienced in being alive. Neither seemed to offer a truly human liberation for men and women together.

By the time I met Andrew Cohen, I had come to a point where my fire for women's liberation was nearly extinguished by cynicism. In my own research, I was more convinced than ever that questioning gender meant questioning the roots of society itself. The questions raised by the women's movement twenty years (and longer) ago went to the core of everything in society. Gender holds the heart of culture. No wonder it was so difficult! I had come to understand the mechanisms by which we become psychologically almost inextricably attached to our identities as men and women. So much, but how much I didn't know, of who we think we are came from cultural conditioning. Because we, as males and females, had such different experiences of culture, our psyches were differently shaped to fit into culture and so created us as if from different planets.

But there seemed to be no way out. I watched friends from the movement turning away from consciousness raising and collective action into a soothing "gynocentric" form of goddess spirituality. I found myself withdrawing from leadership as I saw feminism become a respectable profession—just another job—through which women competed (particularly with each other) for attention and power. The rifts between women of different classes and different racial/ethnic backgrounds seemed almost wider than ever before. I felt despair over the fact that I had never worked with a group of women who

truly supported and trusted each other. So many of my friends were either stay-at-home moms or holding interesting jobs while having primary caretaking responsibility for the kids. They said it was just easier that way; besides, their husbands weren't really interested. Our identities as women had become ingrown, turned in on themselves so that more than ever we identified with being women and hung on to whatever we felt that should mean. The questions were still so important, the stakes so high, but I didn't see any answers.

My first actual meeting with Andrew Cohen came about after being interviewed for this magazine several years ago. From that experience, I knew that Andrew had a commitment to women's freedom that was very unusual. I went to a one-day retreat that Andrew was leading in New York City and had a short conversation with him afterward. During the retreat, Andrew spoke a little about what he was discovering about gender conditioning—and each time he did, I almost leapt out of my seat because I was so thrilled. In my entire life, I had never been more nervous about meeting a person than I was in meeting him. Our meeting was fairly short—mostly because I was so anxious—but it had an extraordinary impact on me. During our talk, Andrew spoke passionately about his commitment to women's real and profound liberation. He invited me to join him at a longer retreat if I found what he was saying interesting.

I found what he was saying more than interesting; it stirred something deep within me. Reflecting on the conversation, I realized what a huge commitment Andrew was making. Thinking about my experiences with Christianity and Buddhism, while I knew that both Christ and the Buddha taught men

and women (which was extremely radical at the time), neither of their legacies has made a commitment to ensuring women's freedom. In fact, in my own family, I had seen how Christianity had become a rationale for accepting oppression.

Oh my god, I thought,

he's really going to take this on. I was deeply moved. Suddenly, I had the sense that the two main forces in my life—women's liberation and spiritual seeking—might be connected in some very real and mysterious way.

Later, I realized that my experience of meeting Andrew was the first time I had met with a man (or woman) in a position of authority who respected me completely as a human being and wanted nothing from me except for me to express my full humanity. I was actually stunned by that realization. Andrew's radical idea is that men and women

both are human beings—and the reality of being a human being takes us far beyond anything that I could imagine. But it is always available to be experienced. I

had to be in this. I realized that to not join Andrew in moving toward freedom for women, and women and men together, would make a lie out of my entire life.

I did go on a longer retreat with Andrew (more than one, in fact). And I have the extraordinary privilege to be a student of his. As students, Andrew has asked us to come together as women—to make real the promise of sisterhood that is the lost soul of the women's movement. I am often reminded in this of the consciousness raising that first broke the isolation of my experience years ago. It's only by coming together that something can change because our separation—from both a spiritual and cultural perspective—is what holds everything in place. And I've come to see my own experience as women's experience in a way that radically implicates me and who I have thought myself to be. Through Andrew's commitment to the freedom of women and men together, the revolution is finally alive and burning. In the following pages, Andrew reveals far more than a radical idea. He reveals a radical reality that challenges each of us individually and collectively to go beyond our known identities into the revolutionary heart of an unknown possibility for human being that destroys separation and otherness. There may be nothing else on the planet more important than this.

she was, was a victim and my father, as sweet and funny as he could be, really wanted it that way—even to the point of getting pleasure out of his dominance. Even as I sided with my mother, I never lost touch with the pain evident in my father's stance of domination. Women's liberation obviously had to be a movement to liberate women and men from the distortions and limitations that turned us into dangerous strangers, the Other to each other. From where I stood, it never was a competition between women and men. It wasn't a zero-sum game: If women win freedom, men then lose. Yes, we were often angry (and some of us, unfortunately, still are) as we came to see just how deep and how oppressive is this system accurately called "patriarchy." And that anger was often directed at men. But feminism's radical idea didn't mean that men were either the enemy or the standard for human being. To me, it meant that I knew in the deepest part of myself that what was happening between men and women, who men are and who women are, had to change and could change. And that it would transform life as we know it.

she was, was a victim and my father, as sweet and funny as he could be, really wanted it that way—even to the point of getting pleasure out of his dominance. Even as I sided with my mother, I never lost touch with the pain evident in my father's stance of domination. Women's liberation obviously had to be a movement to liberate women and men from the distortions and limitations that turned us into dangerous strangers, the Other to each other. From where I stood, it never was a competition between women and men. It wasn't a zero-sum game: If women win freedom, men then lose. Yes, we were often angry (and some of us, unfortunately, still are) as we came to see just how deep and how oppressive is this system accurately called "patriarchy." And that anger was often directed at men. But feminism's radical idea didn't mean that men were either the enemy or the standard for human being. To me, it meant that I knew in the deepest part of myself that what was happening between men and women, who men are and who women are, had to change and could change. And that it would transform life as we know it.